An artist not like the others – Interview with Joan Marie Kelly, artist, social anthropologist, ethnologist and an activist.

Joan Marie Kelly is a talented artist with a big heart. She is socially engaged and like to help others either it’s through her social engagement, her teaching or simply through her artwork. We had a chance to meet with her, and ask her many questions. Now we will leave the floor to Ms Kelly and you will learn more about this talented artist.

Q; You are a woman of many talents. Could you please tell us a little about yourself?

Thank you for this complement. I’m a product of the changing society in which I grew up. As a young person I lived in the USA during the changing roles of women which led to almost all of my friends parents to divorce including mine. Because women forging new pathways and single parent homes were so new, none of our parents were able to handle this well. But this situation created very independent people who sought out their own path without the restrains of family pressure to meet certain ideals. This situation gave me the ability to look around myself and utilize my resources.

One of the most fulfilling things I accomplished in my life happened in this way. I walked into a long-term care medical facility in Baltimore USA, to drop off sketches for a mural I was commissioned to do in a nurse’s home. I was surprised to see so many people around the perimeter of hallways slumped over in wheel chairs. I went back the next day, gathered about 10 persons in a hallway and gave them each a piece of clay. I taught them simple hand-building techniques. If the work told a story, such as asking them to make a piece that answered the question, what is home, I could get publicity. With publicity I got funding. From the hallway I began hiring other artists and move to a larger space. This program is still functioning today.

Q: You are an American artist, teaching art to young students in a well-known art institution in Singapore. It is quite an unusual career path. How did it come about?

I’m American of Irish heritage and have an Irish citizenship too. I never meant to get the job in Singapore. In 2005 I was about to graduate with my Masters in Fine Art when I was on the web and saw an article about the first art degree program in Singapore. Curious, I decided to take a look. I probably looked because I was no stranger to Southeast Asia. When I was 20 living in New York City, I was attending art school during the day and waiting tables at a private arts club at night. At that time the kitchen staff and wait staff were Indonesians. Many of them had jumped ship from a Dutch cruise lines in the New York harbour. Needless to say they were working “under the table”. I was very impressed with the men, who were very smart, and hard working. I admired their sense of humor, very funny yet never laughing at someone in a hurtful way. They always gave me a new perspective. This was before all of the digital communications. These were the days of “travellers Checks” . Therefore it was difficult to send money back home to their families. So I said I would go for them. I wanted to see Indonesia. Armed with a few phone numbers, addresses, envelopes of letters, money and photos, I went down the island of Java and met these impressive loving families, bringing the news of what life is like in New York for their sons.

That day before graduation when I saw the article of the new art school, I took a look at the curriculum. To my shock this was an art school with no drawing courses. I decided to write them a letter just to give them a piece of my mind. Drawing is the basis of all visual communication…my letter went on. I pushed send, and forgot about the letter. About a month later I received an email from the School of Art Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University inviting me to apply for a position teaching drawing. I was in Singapore two months later doing exactly that.

Q: When we look at your artwork, we feel that you are a socially engaged artist. Why do you like to paint the forgotten ones in society?

It’s complex, there is not a simple single reason. I’ll refer to an artist and good friend Sarah Schuster, who wrote about my work. She captured how I feel. She wrote that I learned to use my tools as an [1]artist to chip away at the boundaries that society erects stratifying class, sexuality and economics to assure power to some and powerlessness and lack of agency to others (Schuster, S. 2019)

I’ll refer back to that first trip to Indonesia. One of the families I visited had fourteen brothers and sisters. I noticed that the oldest and darkest skinned brother would not enter a room in the house if I was there. The whole family would watch TV at night. As we all sat, gathered in the room, the older brother would sit outside watching through the window just behind my head. This confused me and made me very uncomfortable. I knew I had to change this somehow.

The father was eighty nine years old and was the spiritual leader of the community in Bandung Indonesia. People came to the house to have their dreams read. I thought he was remarkable because his son in New York told me that his father said to him when he came of age, that he was not to learn the traditional martial arts, he was to go to college. His weapon was his smile. I am still stunned that a man in the middle of Java in 1983 could have the vision to see how the world was changing but more than that the ability to accept and adapt from cultural traditions to an unfamiliar changing world. Today it’s a rare person who has the skills to accept change and adapt.

I had to solve the situation of this darker son sitting outside while I was in the room. I decided to ask the father if I could paint his portrait. He said yes. It was a small life sized portrait of only his face but I was lucky it was one of those times when everything fell into place perfectly. The father never spoke to me except for when I told him I was finished. He came around to the front of the painting for the first time, looked at it and said I’m the Grandfather and I’m eighty-nine years old, in Bahasa Indonesian. The family contacted me years later to say Ian had died and for the lack of a photo my painting was use in a procession at the funeral where 3000 persons attended.

This experience was when I first realized my skills as an artist have the power to interact across boundaries creating an empathetic engagement. By acknowledging the Grandfather in the painting, I acknowledged the whole family. I see them and they see me. Posing is not a passive activity. As the portrait artist and the sitter stare at each other, scanning over and over again for hours, sight becomes a form through which to know each other. Creating this experience between us minimized our differences. It was many years later when I began the position at Nanyang technological University I picked up this thread in Southeast Asia using my creative skills to navigate my status as a foreigner.

In Singapore I began to use my skills as an artist in collaboration with different scholars. I discovered that portrait painting was very effective in breaking barriers when scholars are doing research in ethnic communities. By the way, an artist always pays their model unless it is a commission or they are giving the painting as a gift. Communities need support so the money from modelling is very welcome. The community sets the price. Usually the community thinks of themselves as the one who performs labor not the Senior Lecturer from a university in Singapore. Often they are an agricultural society along with selling traditional crafts to tourists. But after watching me sweat in a refugee site or inside a sticky brothel every day for two weeks, we have another common ground: labor, and my labor is focused on them. We are in this project together. The entire community gathers around, usually seeing the person posing in a new role, as the center of attention. The painting is the reason for our encounter. We stare at each other. It’s a process of recognition and identification. I’m out of my safe space and enter unfamiliar spaces of the community. Usually the sitter will prepare and get dressed up as they want to be seen for their portrait.

Sarah Schuster explains about my artwork: One remarkable property of our vision is that what we gaze upon is drawn to look back at us, so as the painter looks she draws the sitter to look back and both engage in the process and experience of the other. In the end, the portrait is neither artist or subject, but both and something new. (Schuster, S. 2019)

Through observation and conversation I come to know something of the sitter. As the portrait develops I discover parts of the model within myself, similarities that then highlight our differences. I come to know the model through relationship and the painting is what we are together…it is something new and never complete. Our relationship becomes a third entity, unfixed but connected to our encounter and then this takes on an endless sequence of relationships each time the painting is viewed.

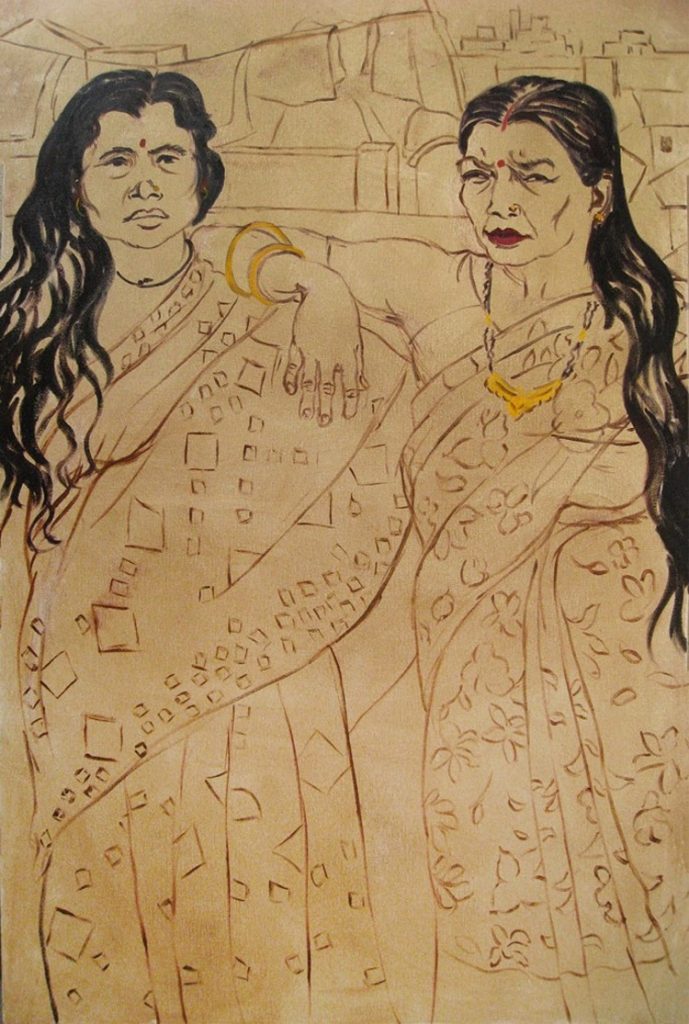

Q: You are also participating in quite an unusual project: giving voices and a picture to some of the most forgotten and disparaged women in society, the prostitutes. Could you tell us a little more about this project, and how you got involved?

It was fifteen years ago 2008 when I met Bhaskar Mukhopadhyay, a cultural theorist from Calcutta and teaching at University of London Goldsmiths. After I made a presentation he slipped his card to me saying “I want to bring you to Calcutta.” Bhaskar was doing research on sex workers. He asked me to paint their portrait giving him a good amount of time to interview the women while I painted. I agreed. This is the first opportunity I had to work with a scholar and understand just how valuable art making can be as a research methodology.

We planned the trip but just before the date Bhaskar could not come. Instead he arranged his friend an artist and scholar Amitava Malakar, Malu for short, to work with me in the brothel. For the first meeting, he set-up a night where we would meet a certain sex worker who he though could possibly organize our project. She would need to organize all the women that we would paint each day. Malu said she was an amazing cook so we would try to arrange that she would also prepare lunch for us each day. Because I had no idea about the social context of the brothel, there was so much more she had to navigate to making our project happen that I was unaware of. The first night, Malu brought a few beers interpreted between us all and we had a little party in Shikha’s room. Shikha and I hit it off well. Of course they wanted to know why I wasn’t married. We all agreed when I told them men were big problems! When they asked me about my last boyfriend, I told them a story of how he fell head first into a well and was impaled by the deer antlers at the bottom of the well. He lived. They took this to mean that it happened to him because of me. They said men should stay away from me because I’ll put a curse of bad luck on them, such as what happened to my ex.

I was in the brothel in 2008 for a month, not every day but I spent a lot of time there. I saw the good the bad and the ugly. The good was the humanity between the women. At that time they all had young children and took care of each other’s children from watching them to feeding them as their own. They would be jumping around me while I made the paintings and drawings. I had to work hard to concentrate. I brought them markers and paper, and yarn for some of the women who wanted to knit.

The women protected each other. They always left their doors unlocked so that if they heard fearful sounds from a woman in one of the rooms, 3-4 of them would barge into the room, all beating the man at once. It is a women’s community. The NGO was corrupt. It was amazing to me that for women that made so little money performing the act of intercourse, there were vultures circling at all times to get a piece of that tiny money.

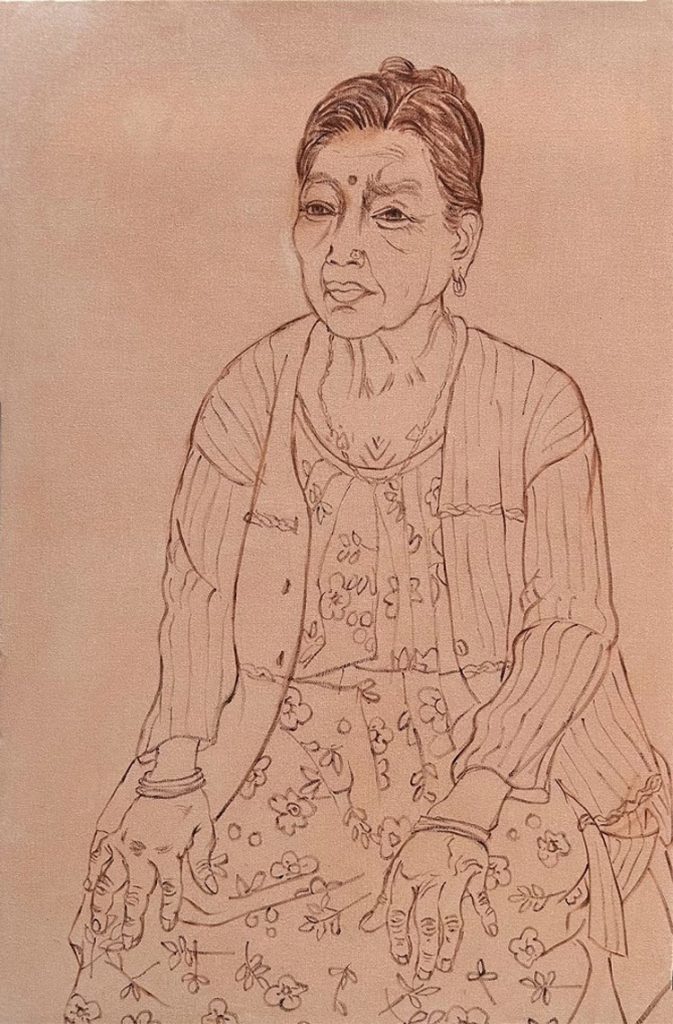

Most of the women hated men. Shikha was born in the brothel so she had a different experience. She was never betrayed and sold to the brothel by a husband or neighbor at a very young age 11 to 13 years. This is the story of most of the women at that time. Their family in the village barely had the means to survive. They were told there was a job in the city. Their families couldn’t feed them, therefore they let them go. Or they married them at that young age. Instead they were brought to a brothel where if it was known back in their village that they had lived and worked in a brothel they would not be accepted back into the family. Consequentially unaccepted in society they stay in the brothel. Their lives are full of sadness and in turn depression. That is what I found going back 15 years later and drawing some of the same women I had known in 2008. In 2008 every woman put on her saree to be painted. In 2023 only one did. They didn’t care what they looked like. There were only a few children. Most of the same women were in this same brothel. Their children were off on their own or very frequently told me they had died of alcoholism or something else. Many of the women now just waiting to die. Others were doing well.

They place men in three categories, takers: take all your money, eaters: eat all your food and givers: give and take care of the women. Out of the eighteen women I painted this year 4 described having lives with a giver. They were basically happy. Three of those the man had recently died but they had not had to work in the sex trade for many years. He provided for them. Now they are making money by renting their rooms by the hour, to younger women living outside the brothel. Their husbands lost their job or is an alcoholic, they have 2-3 kids and need to feed them. These young women as the sole bread winners, choosing as their best option to work in a brothel as a means to feed their families was a very bad sign to me about the state of society. Fifteen years ago all the women were living there. These young women don’t live their but choose that sex work is the best thing they can do with their means and situation. That I found frightening. I really enjoyed seeing all the women again. They all remembered me and asked if I’ll come back in another 10 years and paint them again. It was touching. They had photographs of me and I of them. They showed me pictures of me with their children and now introduced me to that same son’s wife.

For me going into a brothel in Kolkata India was a very foreign concept and place in every way. As the women spoke and Malu interpreted I shocked as to the way they framed their experiences. Sex being such a different experience of exchange for my life. I had to figuratively wash out my cultural conceptions and experiences about sex and intimacy as I tried to understand how they felt and made decisions. I was very interested. I wanted to understanding and be able to see from their point of view as much as possible. The women were direct. If you’re going to be raped everyday by a husband you might as well be paid for it. It’s reasoning such as this that jolted me into the world of these women.

Q: Do you think that art is being forgotten or at least neglected in our modern societies, and if yes, what should the role of an artist be in your opinion?

There are still people making art but it is being neglected in the way that society is not making a pathway for artists to survive. The cost of living is too high everywhere. It used to be that an artist could “live between the cracks.” If they didn’t need too many material goods they could lead a modest life and make art. Now to pay the rent, one must have a corporate job. Young people see that they can’t make ends meet being an artist therefore the enrolment in art schools has dropped off considerably in the USA. Many degree programs have closed and others merged with universities in the vicinity. This state has narrowed the pathways in which an artist can led their lives.

I think this has caused widespread depression in young people because they see very few ways they can lead a life with an alternative narrative.

There is need for artists in society to take on many roles. The artists is the sense maker, the conscious of society. The one to seek beauty. The one to ask hard questions and make disparate connections. The artist creates engagement between people where there is no social or physical infrastructure to communicate.

Q: You were invited to take part in a conference in Baghdad, Iraq, recently. What do you consider the main outcome on a personal level?

An American doesn’t take an invitation to Iraq lightly. I carry a deep sense of remorse for the actions my homeland has imposed on the Iraqi people and their land yet I would not know there was that history between us from how welcomed I felt the entire week of the conference. I found the Arab people so inclusive and warm. The amazing thing is they party, dance and have lots of fun without any alcohol. Spiritually, I felt they are a very healthy people.

I was glad for the opportunity to hear so many points of view from people I don’t often get direct contact with and I was happy to share my work of drawing and storytelling as tools to address trauma due to environmental disaster. Through language and cultural differences the people at the conference put effort into reaching out across all of these barriers.

Q: Finally, if you have a message to our readers what would that be?

It’s very difficult to make assumptions about people.

2016 I had the opportunity to create an art program in a girls prison in Morocco for girls 9-18 years old. I witnessed the transformative power art making could give to the girls. The work creating a new identity for the girls to see themselves as artist instead of the bad girl in prison. This lead me to study under Dr Richard Mollica at Harvard University Global Mental Health: Trauma and Recovery Certificate Program and York University’s Summer Course in Refugees and Forced Migration. From there I began working to Visualize the Impacts of Shock & Collective Trauma by developing trauma-informed art making and storytelling workshops for earthquake survivors in Türkiye. Along with a team from Balikesir University and support from the Balikesir Municipality we created a series of storytelling workshops in the summer of 2023. Over the years of experienced I’ve refined a developmental process using drawing and stories to create a safe and empowering space where people, irrespective of their backgrounds or previous engagement in art, can explore their personal narratives and find strength in self-expression. I hope to continue to have new opportunities to develop this direction and contribute to the lives of individuals affected by trauma by being a catalyst for hope and recovery.

- [1] Figure 1 Painting by Joan Marie Kelly 1983. Figure 2

- Photo Credit: Isabel Löfgren

- Photo Credit: Roshni Sonkar 2023

- Left: Rt is a woman I drew in 2008

- The same woman I drew in 2023