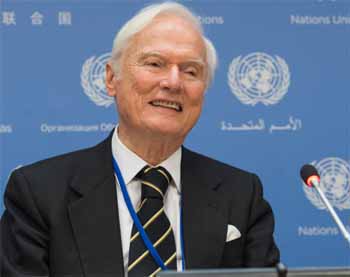

Interview With Ambassador Idriss Jazairy, Executive Director, Geneva Centre for Human Rights Advancement and Global Dialogue

Q: Ambassador you have a long and impressive career. First of all, could you tell us a little about yourself ?

I am currently the Executive Director of the Geneva Centre for Human Rights Advancement and Global Dialogue, a think-tank holding special consultative status with the UN. I have held this position since July 2016. I was previously a Board member of the Geneva Centre.

Prior to my current professional role, I represented my native country Algeria through different functions: After having served as a Presidential Adviser to the former President of Algeria Houari Boumedienne for 7 years, I was nominated as Ambassador of Algeria to Belgium, the USA, the Holy See and the UN office in Geneva.

At the inter-governmental multilateral level, I was elected in 1984 and subsequently re-elected President of the International Fund for Agricultural Development, a Rome-based UN specialized agency which plays a major role to scale up rural development and to enhance the social and economic empowerment of poor people. I have also held other functions in the field of international relations and human rights; in 2009, I was the President of the Conference on Disarmament. The following year, I was the Chairman of the Council of the International Organization for Migration.

I have also devoted part of my career to civil society. I served as the Executive Director of ACORD – an international consortium of NGOs, encompassing Oxfam, Novib (Netherlands) and CCFD (France) among others. We carried out numerous projects and initiatives to enhance the protection and empowerment of victims of civil strife in Africa. From 1995 to 1998, I was a member of the Board of CARE/USA.

In addition to my current function as Executive Director of the Geneva Centre, I am also the UN Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of the unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights.

Q: Looking back at, what is the position that gave you the most personal satisfaction?

The first position that gave me greatest personal satisfaction was that of President of the International Fund for Development where I led this specialised agency of the United Nations to develop approaches to empower the rural poor and in particular smallholder farmers and their husbands. Poverty was not their fate but just reigned in the imagination of international who were unable to see this low level of income could signal an untapped potential that needed to be unleashed. Following on the footsteps of my eminent predecessor, Abdul Mohsen Al Sudeary, I was put in the position of being able to unleash this potential, thus demonstrating that those rural dwellers who were seen as a burden on society were in reality its “New Frontier” of development. This is how we developed our innovative and unorthodox approach to micro-credit, replacing assets as collateral by group solidarity. We pursued this policy consistently throughout Africa, Latin America and Asia. The setting up of micro-credit clubs soon became the trigger that unleashed the productivity of smallholder farmers and rural dwellers. We applied this approach in particular with the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh whose Director obtained a Nobel prize through the success of the plan we put in place together. Our initiative heralded a new era of micro-credit worldwide and even in developed countries including the US.

The second position that has given me great satisfaction is that of Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on the adverse impact of unilateral coercive measures. The latter are the sanctions that individual States or groups of States apply to targeted States, usually but not always developing and weaker countries, without the seal of legitimacy of the Security Council. It was in this capacity, that I, together with my colleague, Aristide Nononsi, the Independent Expert for the Sudan, were able to negotiate through quiet diplomacy between the Sudan and the US the progressive lifting of sanctions which had been imposed on the Sudan for over two decades. They were finally lifted in September 2017 after a year and a half of sustained good offices by our two mandates. This is the measure of what mandate-holders can achieve through fostering good will and not just by naming and shaming concerned States.

Q: You were the Special Rapporteur of the UN Human Rights Council on unilateral coercive measures. Could you be so kind to tell us what that’s all about. Do these measures have an impact, if yes what would that be ?

On 26 September 2014, the Human Rights Council adopted resolution 27/21 and Corr.1 on human rights and unilateral coercive measures. The resolution stresses that unilateral coercive measures and legislation are contrary to international law, international humanitarian law, the Charter and the norms and principles governing peaceful relations among States, and highlights that on long-term, these measures may result in social problems and raise humanitarian concerns in the States targeted. Highlighting the deep-rooted problems and grievances within the international system and in order to ensure multilateralism, mutual respect and the peaceful settlement of disputes, the Human Rights Council decided to create the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights. At the 28th session of the Human Rights Council, I was appointed by the latter as the first Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of the unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights. I took office of this important function on 1 May 2015 for a five-year mandate which was renewed in September 2017.

The adverse effects of international coercive measures in general on the enjoyment of human rights of targeted populations have been widely documented. The question arises whether extraterritorial sanctions display specific features, i.e. whether they are likely to have specific adverse consequences on human rights, that can be distinguished from those arising from the use of sanctions in general. Such specific effects flow from extraterritorial sanctions, to the extent that they affect the ability of the targeted country – and its population -, as well as that of third countries not involved in the dispute between source and target countries, to interact with the global business and financial community. Most international businesses, while legally not subject to the jurisdiction of the targeting State, will in practice be unwilling to entertain any economic relations with parties in the targeted State that might lead to their “violating” the provisions of the extraterritorial sanctions regime — and thus might jeopardize their ability to pursue their own business activities in the targeting State. This has led to the damaging practice of over-compliance by trading partners of targeted countries. The result is a de facto blockade of the target State, voluntarily complied with by economic actors that are not even legally subject to the jurisdiction of the targeting State. The distinct additional impact of extraterritorial sanctions may also be related to their effects on the targeted State’s ability to gain access to international financial institutions, foreign financial markets and international aid.

Extraterritorial application of unilateral sanctions may also have an adverse impact on the enjoyment of human rights in third countries, which are not targeted directly, but are prevented by the operation of the extraterritorial foreign law from entertaining economic relations with the target country.

Q: You are the Executive Director and founder of the Geneva Centre for Human Rights Advancement and Global Dialogue. How did you get the idea to set up this organization ?

The Geneva Centre was established in 2014 by our Chairman HE Dr. Hanif Hassan Ali Al Qassim. The Centre was set-up with the aim of promoting global dialogue and offering an alternative narrative on issues related to the promotion and to the advancement of human rights in the Arab region. Another driving factor behind the decision to create the Centre ambition was to act as a platform for better understanding between a variety of stakeholders involved in the promotion and protection of human rights. The Centre’s vision is therefore to build on such an understanding and to promote tolerance and mutual respect among peoples and regions.

Q: What are the objectives and the mission of the organisation ?

The Geneva Centre is a think-tank dedicated to the promotion of human rights through cross-cultural, religious and cross-civilization dialogue between the Global North and the Global South, and through training of the upcoming generations of stakeholders in the Arab region. The Centre works towards a value-driven human rights system, steering clear of politicisation and building bridges between different narratives thereon of the Global North and of the Global South. Our objective is to act as a platform for dialogue between a variety of stakeholders involved in the promotion and protection of human rights. The Centre advocates giving human rights due recognition in governance throughout the world and aims to promote mutual understanding and cooperative relations between people.

Q: You are the author of several publication. Are you working on something now ?

The Geneva Centre pursues its mandate through the organization of panel debates at UNOG, the publication of studies and the organization of training courses. The Geneva Centre’s studies address issues of importance to stakeholders in the Global North and the Global South. The aim with our publications is to offer a depoliticised view of human rights issues and to promote the principles of understanding, constructive humanistic dialogue and respect of others. This is at a time when human rights are being politicized and invoked selectively to embarrass political foes. In the Centre’s publications, we analyse the outcomes of panel debates held at UN Geneva where we identify points of communalities and mutual enhancement in the aspirations of decision-makers – in the Global North and in the Global South – to promote and advance human rights. The summary records of the panel proceedings are then followed by an intellectual think piece where we identify lessons learned and points of guidance to stakeholders.

As of August 2018, the Geneva Centre’s publications include :

- (1) In defence of Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council: An alternative narrative from the South

- (2) Islamophobia and the implementation of UN Human Rights Council Resolution 16/18: Reaching out

- (3) De-radicalisation or the roll-back of extremist violence: Proceedings of the panel meeting

- (4) Muslims in Europe: The road to social harmony

- (5) Women’s rights in the Arab region: Myths and realities

- (6) The right to development, 30 years later: Achievements, challenges and the way forward

- (7) Islam and Christianity, the great convergence: Working jointly towards equal citizenship rights

- (8) Human rights: Enhancing equal citizenship rights in education

Moreover, the Geneva Centre has organized many other panel debates at the UN to promote and advance human rights in the Arab region. Staff of the Geneva Centre, under my supervision, are currently preparing follow-up publications to panel debates that were organized in 2017 and in 2018.

The following publications will be issued during the course of the year :

- (1) Religions, creeds and value systems: Joining forces to enhance equal citizenship rights: 25 June 2018

- (2) Protecting people on the move: Internally displaced people (IDPs) in the context of the refugee and migrant crisis: 21 March 2018

- (3) Improving access to justice for workers: the case of UAE: 20 March 2018

- (4) Veiling/unveiling: The headscarf in Christianity, Islam and Judaism: 23 February 2018

- (5) Migration and human solidarity: A challenge and an opportunity for Europe and the MENA region: 14 December 2017

- (6) Women’s rights in the Arab region: Between myth and reality: 15 September 2017

Q: Based upon your experience, what advice would you give to the younger generation ?

In view of the current circumstances and the contemporary tensions being played out in the Middle East, North Africa and in Europe, I strongly appeal to the younger generation to rediscover the common values of societies in Europe and in the Arab region.

We are now witnessing the rise in extremes on both sides; the surge of xenophobic populism in Europe and the upheaval of extremist militancy in the Arab region. In Europe, the adverse impact of globalization and the financial crisis have given rise to the notion of a lost generation in which Europe’s youth experience a greater degree of impoverishment, inequality and unemployment. Populist parties have taken advantage of this social vacuum by relying on fearmongering and scapegoating of exogenous groups –such as migrants and refugees – to provide legitimacy to their political ideologies. They have become credible political actors in many countries and have succeeded in gaining electoral support in local and national elections.

In the Arab region, the collapse of post-independence ideologies, geopolitical power games and proxy wars have left a social and political vacuum that has been filled by terrorist groups instrumentalizing religion in their search for legitimacy. Extremist violence cause widespread indignation fuelling indiscriminate xenophobic responses that undermine national unity. This feeds the recruitment propaganda of extremist groups. The persistence of political and social unrest in the Arab region have become the main drivers of poverty, societal decline and instability. Without prospects for a stable future, youth – at an early stage of their lives – therefore become prone to despair.

In this connection, the best starting-point to address and roll-back these ominous trends is to identify points of commonalities between Abrahamic faiths on which future generations can pin their faith to promote solidarity and greater understanding. This new narrative – that we belong to one humanity and have a common starting-ground – would enable youth to protect themselves from heinous ideologies that foster social division and split up societies. All world religions converge, with 10% specificity, and 90% similarity. However, we tend to focus on the 10% that divide humanity instead of using the 90% as a common starting-point for humanity to promote peace, tolerance and leading to true empathy in diversity.

It is essential therefore to help the current generation discover that they can develop a sense of well-being and fraternity through communities of faith and by broadening the space for common purpose and mutual understanding. This could eventually contribute to the promotion of peace, social justice and inter-religious harmony between and within societies. Only through dialogue between populations and regions of all cultures and religious faiths can bridges of understanding be built between them, thereby fostering social cohesion and harmony. We as decision-makers have the moral responsibility to offer youth the building blocks to create a common future in the interest of humanity. It we can build together and identify a common path for the future, we will be able to better appreciate one another and to live in peace and in harmony.

Geneva, Oct 2018